Education

Funding structures, not union politics, driving teacher pay

November 21, 2019

Curtis Shelton

Executive summary

This paper shows the difference in teacher pay and spending on instruction between representative school districts in Oklahoma and Texas. It then examines two factors that might contribute to such divergence: sources of available funding and laws related to labor unions. The findings show that Oklahoma’s stronger unions do not correlate with higher pay for teachers—just the opposite. What could explain Texas school districts' ability to pay teachers more is a different funding model that relies more on local revenues.

Introduction

During 2018, many Oklahoma school districts shut down for up to two weeks as part of a union-led walkout campaign targeting the state legislature. Just days before the shutdown, the legislature had passed a package of tax increases in order to raise teacher pay by an average of $6,100. One of the most salient arguments leading up to the pay raise and walkout was that Oklahoma was losing teachers to Texas due to higher pay south of the Red River.

It is true that Texas, on average, has paid teachers significantly more than Oklahoma. Teachers in Texas also pay no income tax, while those in Oklahoma pay a five percent tax on their paychecks. How does the Lone Star State achieve these higher rates of pay?

This report examines a representative sample of ten school districts in each of the two states, as well as collective bargaining laws for school districts in the two states. It shows the pay differences within each state as well as between the two states. Because the most significant difference in how the two states finance education is in the area of local funding, which comes from property taxes, this report examines those tax rates within the school districts.

Note that due to lag time in the availability of these data, they come from before Oklahoma’s 2018 and 2019 statewide teacher pay raises took effect. This means that today, Oklahoma’s average teacher pay should be about $7,320 higher. The 2018 pay raise varied within each Oklahoma district. Pay will have risen based on that district’s mix of teachers—the raise for a starting teacher was $5,000, but the raise for the most senior teachers with advanced degrees was over $8,000. The 2019 pay raise was an across the board pay raise of $1,220.

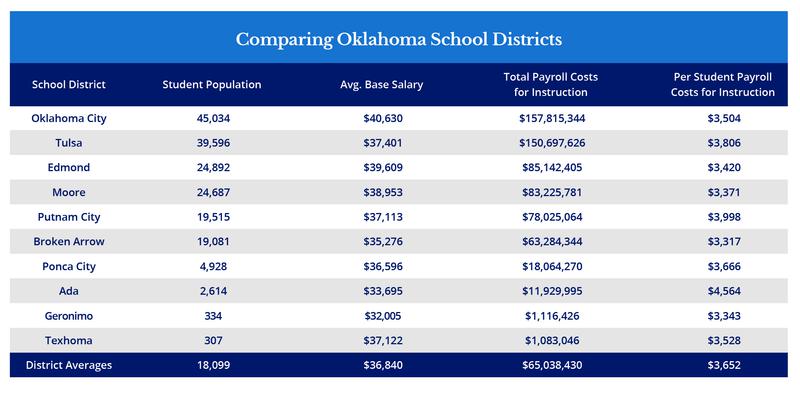

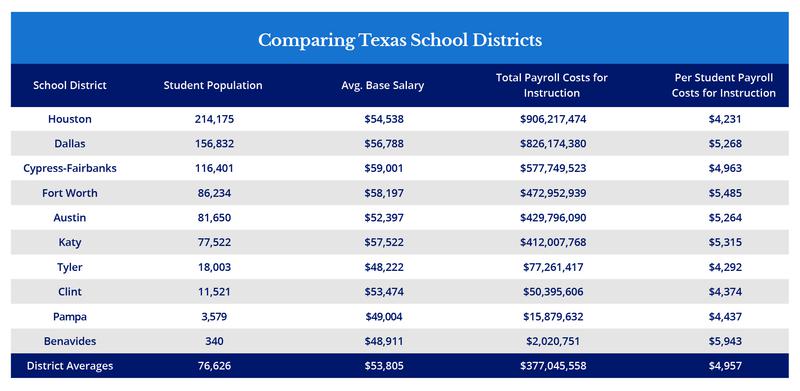

Teacher pay and payroll costs per student

Of the 10 districts researched in each state, the average salary in Texas was $53,805[1] while the average salary in Oklahoma was $36,840[2]. There was a greater difference between the districts with the lowest and highest pay in Texas than in Oklahoma. In Texas, the Cypress-Fairbanks school district paid an average annual salary of $59,001 while the Tyler district paid $48,222, a difference of $10,779. In both states the teachers in larger districts tended to make more than those in smaller districts.

Salaries, however, are just one part of total compensation. The school districts provide other monetary benefits. Because the available data from Texas do not separate teachers from other instructional personnel, we have used total payroll costs for instruction, which include salary and other benefits, to compare between the different districts in each state.

The Texas districts on average spent $4,957 per student on payroll costs for instruction while Oklahoma spent $3,652. Again, Texas has a wider variance, with the Benavides district spending the most, $5,943, and Dallas spending just $3,016. The Oklahoma district spending the most on instruction costs was Ada at $4,564 while Broken Arrow spent $3,317 per student on instruction.

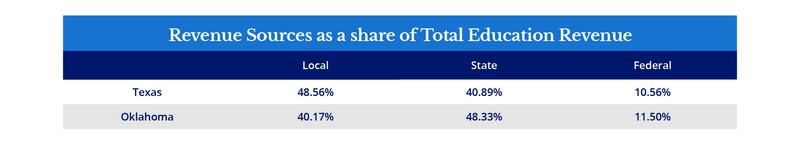

State versus local revenue sources for school districts

One of the major differences between Oklahoma and Texas is how the states fund education. State sources provide 48 percent of total revenue for education in Oklahoma. Texas relies more on local revenues, with 48 percent of Texas’ total education revenue coming from local sources. The breakdown between state, local, and federal revenue sources can be seen in the chart below.

Much of Oklahoma’s local revenue is restricted to district building funds and repaying bond debt that was incurred for capital improvements. Texas has fewer restrictions on its local funds, allowing more of that funding to go to operational expenses, including instruction. This likely explains why some large districts in Texas are able to pay teachers more, thus raising average teacher pay for the whole state.

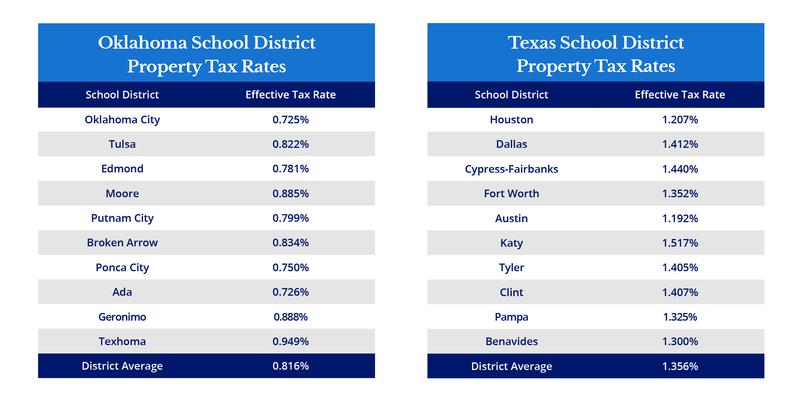

Property taxes at the school district level

Oklahoma levies a much lower property tax than does Texas. While the rate is not uniform across either state, the Texas districts on average have an effective tax rate of 1.356 percent. These rates vary from 1.517 percent in Katy to 1.207 percent in Houston. The average effective tax rate for Oklahoma districts was .816 percent. These rates ranged from a high of .949 percent in Texhoma to a low of .725 percent for Oklahoma City.

Collective bargaining laws in Texas

Both Oklahoma and Texas are right-to-work states, which means no person can be compelled to join a union as a condition of holding either a government or private-sector job. The similarities end there.

In Texas, collective bargaining is explicitly illegal. The Texas Government Code, Section 617.002, says

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING BY PUBLIC EMPLOYEES PROHIBITED. (a) An official of the state or of a political subdivision of the state may not enter into a collective bargaining contract with a labor organization regarding wages, hours, or conditions of employment of public employees.

(b) A contract entered into in violation of Subsection (a) is void.

(c) An official of the state or of a political subdivision of the state may not recognize a labor organization as the bargaining agent for a group of public employees.

The next section prohibits any kind of strike or walkout, and states that an employee who violates this rule “forfeits all civil service rights, reemployment rights, and any other rights, benefits, and privileges the employee enjoys as a result of public employment or former public employment.” This could include forfeiting health and pension benefits.

Since collective bargaining is the raison d'être of unions, Texas law presents a de facto ban on government employee unions. While Texas does have teacher organizations that call themselves unions and affiliate with the American Federation of Teachers, they do not operate as unions because they do not collectively bargain with school districts. They have no seat at the table, any more than any other political organization, when it comes to negotiating teacher pay.

Collective bargaining laws in Oklahoma

Oklahoma law forces school districts to recognize and bargain with unions. And even though no teacher can be fired for declining to belong to a union, an Oklahoma teacher in a unionized school district is still required to allow the union to represent him or her. Oklahoma Statutes Title 70, Section 509.2 is emphatic: “The board of education shall recognize an employee organization designated by an election of the employees in an appropriate bargaining unit as the exclusive representative of all the employees in such unit.” This guarantees union power in school district governance, the exact opposite of the law in Texas.

Unions in Oklahoma school districts often demand—and receive—guaranteed access to new teachers as a part of orientation programs, use of school mail systems, time to speak in faculty meetings, free use of school facilities for meetings, and paid leave to participate in union activities, including political activities. The collective bargaining agreement in the Oklahoma City district requires the district to pay up to five teachers to work full time for the union.

While Oklahoma law prohibits strikes, the measure is narrowly written. Oklahoma Statutes Title 70, Section 509.8, says “It shall be illegal for the organization to strike or threaten to strike as a means of resolving differences with the board of education.” While not tested in court, this provision is widely understood to allow, or at least not cover, shutdowns targeting the legislature or those instigated or acquiesced to by a local school board. Penalties even for covered strikes are only the loss of pay during a strike. A union found to have organized a strike “shall cease to be recognized as representative of the unit and the school district shall be relieved of the duty to negotiate with such organization or its representatives.”

Because Oklahoma and Texas are different in myriad ways, only limited conclusions can be drawn about the effects of the contrasting collective bargaining laws in the two states. Teacher unions have much less power in Texas—in fact, they do not really exist as unions—than in Oklahoma. Yet teachers are paid more in Texas than in Oklahoma. This shows that other factors are more important to teacher pay between the two states than the presence of unions. It also suggests that any positive impact on teacher pay from unions in Oklahoma is small or nonexistent.

Conclusion

Teacher pay in Texas varied more by school district than in Oklahoma, based on the ten districts examined in each state. Average teacher salaries in the Texas districts ranged from $48,222 to $59,001. The range in Oklahoma districts was from $32,005 to $40,630. After the two teacher pay raises, these numbers should be approximately $39,325 to $47,950. Still, Texas pays teachers more. Spending data for these districts show that the Texas districts spent more than $1,200 more per student on instruction than the Oklahoma districts.

Texas school districts also rely more on local funding than Oklahoma districts, while receiving similar amounts of federal funds as a percentage of total revenue. Average effective property tax rates were higher in every Texas district than any of the Oklahoma districts. This access to local funding, particularly to relatively stable property tax revenues, could explain the ability of the Texas districts to spend more on instruction and thus to pay teachers more than the Oklahoma districts.

Oklahoma law gives special powers to unions within school districts. It allows unions to be the exclusive representatives of teachers in contract negotiations and mandates that districts bargain with these unions. And while Oklahoma law prohibits some strikes, the provision is so narrow it does not apply to shutdowns aiming to influence state-level policy. Texas law prohibits collective bargaining, effectively banning teachers’ unions, and punishes any attempt to shut down schools for political reasons. Yet Texas is credited with attracting teachers away from Oklahoma. The contrast between these two states is ironic given that unions claim to increase the pay and other benefits of work.

The structure of government, particularly the availability of local funding, is more determinative of teacher salaries than the presence of unions or collective bargaining. In some instances, union politics may hamper efforts to raise teacher pay. State legislators who want to increase pay for teachers should pay less attention to unions and focus instead on allowing local districts to raise additional operating funds through local taxes.

- [1] Texas Education Agency Staff FTE counts and Salary Reports https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/adhocrpt/adpeb.html Author’s calculation

- [2] Oklahoma State Department of Education Certified Staff Salary Information https://sde.ok.gov/state-minimum-teacher-salary-schedule#admin Author’s calculation

- [3]

Houston Independent School District Adopted Budget Book 2017-2018 https://www.houstonisd.org/sit...

Dallas Independent School District Adopted Budget Book 2017-2018 https://www.dallasisd.org/cms/...

Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District Adopted Budget https://www.cfisd.net/download...

Fort Worth Independent School District Official Budget 2017-2018 https://www.fwisd.org/site/han...

Austin Independent School District Official Budget Book 2017-2018 ttps://www.austinisd.org/sites/default/files/dept/budget/docs/Budgets/Official_Budget_Book_2018_-_FINAL_VERSION.pdf

Katy Independent School District Official Budget Book 2017-2018 http://www.katyisd.org/dept/bf...

Data provided by Tyler Independent School District through an open records request

Data Provided by Clint Independent School District through an open records request

Data provided by Pampa Independent School District through an open records request

Data provided by Benavides Independent School District through an open records request

- [4]

Oklahoma State Department of Education District Enrollment https://sde.ok.gov/documents/2...

Oklahoma State Department of Education District Reports https://sdeweb01.sde.ok.gov/OC...

- [5] National Center for Education Statistics Revenue and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education: School Year 2015-2016 (Fiscal Year 2016) https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019301.pdf

- [6]

Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts School District Rates and Levies 2018 https://comptroller.texas.gov/...

Oklahoma Tax Commission 17-18 Levy Breakdown

Oklahoma Tax Commission 17-18 State and Co EMR

Oklahoma Tax Commission Fractional Assessment Percentage Ratios 2018