Education

Greg Forster, Ph.D. | November 2, 2021

Oklahoma still segregates public schools

Greg Forster, Ph.D.

The most powerful tool for racial segregation the American government ever had was its school system—not just in the past, but today. A new data-mapping tool from the Urban Institute shows in shocking detail how effective the government school monopoly is, in Oklahoma and elsewhere, at continuing to enforce racial segregation. If we’re serious about aspiring to an integrated society, we need to dismantle the monopoly and give all parents school choice.

The government school monopoly has been segregated by race all the way back to its first creation in the 19th century. America has never had an integrated school system. On the contrary, when the system was created, keeping children of different colors in separate schools was one of its fundamental policy commitments.

That policy has never changed. It’s true that since the civil rights revolution, the government’s school segregation policy has no longer been openly acknowledged for what it is. The system is no longer allowed to segregate by race directly.

The workings of Oklahoma’s segregation system are laid bare in stark images produced by a liberal think tank.

However, the system has continued to use an indirect method to carry on the same policy. Assigning students to schools based on where they live guarantees segregated schools, because Americans live in segregated neighborhoods. And even as the lines that separate school districts and individual school attendance zones have fluctuated over generations since the civil rights revolution, the lines continue to be drawn so as to ensure racially segregated schools.

Should we be surprised at that? As long as government monopolizes schooling, who goes to school where is under political control. And one of the most enduring forms of political mobilization is racial identity pandering. Whether openly or by subterfuge, politicians make gravy by appealing to voters’ race-based anxieties and perceived interests. That reality doesn’t magically disappear when it’s time to draw district and attendance-zone lines.

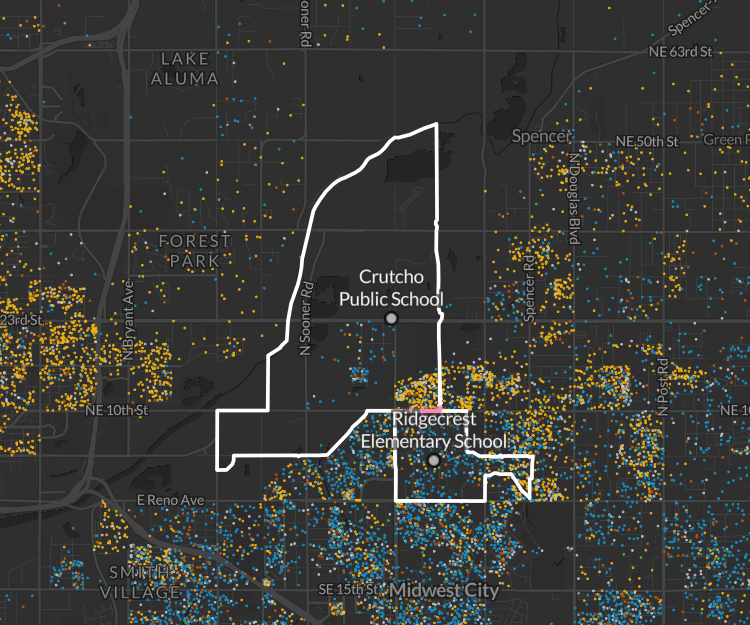

The workings of this continuing segregation system in Oklahoma are laid bare in stark images produced by a new data-mapping tool from the Urban Institute. In a research project titled Dividing Lines, the institute projects population data on the race and ethnicity of the under-17 population onto maps of school districts and attendance zones.

The maps are stunning. Politically drawn lines that determine where students will go to school snake around on the screen. They swerve one way here to scoop up a local population of white students, and the other way there to avoid including another local population of black or Hispanic students.

In Oklahoma City alone, the Urban Institute points to six especially egregious examples of segregated school boundaries. For example, in the neighborhoods near Telstar Elementary, the under-17 population abruptly shifts from mostly-white to mostly-black as you travel either north, south, or east from the school. And what do you know? The attendance zone for Telstar also abruptly cuts off in the right places, on all three sides, to make sure most of the white kids go to Telstar and the most of the black kids don’t.

Especially egregious is the line that separates Telstar from its eastern neighbor Nicoma Park Elementary, in the next district over. The line between them generally runs north-south, as you might expect, but at one point it suddenly turns 90 degrees and runs east-west, then turns 90 degrees again. Why? That might have something to do with the fact that, at that exact point, there’s a cluster of black kids who live further west, closer to Telstar. By suddenly swerving over, the line makes sure those black kids stay in Nicoma Park, where they belong, even though it’s further from their homes than Telstar.

Or consider Crutcho Public School, which is located in a sparsely populated area that’s adjacent to a much more densely populated area. The densely populated area is mostly black, but has a sizeable white cluster on one side. The lines are drawn so that the white kids in the densely populated area go to Crutcho, while the black kids in the same densely populated area are in another district and are assigned to Ridgecrest Elementary and Cleveland Bailey Elementary.

Unsurprisingly, the progressives at the Urban Institute and I differ on the question of how these lines should be drawn if we lived in a perfect world where they weren’t drawn to satisfy political constituencies driven by identity politics. But we don’t live in that world, so who cares? To my mind, the only question that counts is how we can realistically, in this world, break the chain that binds skin color and school attendance.

School choice, which allows parents to use the public funds for their child’s education to attend the public or private school of their choice, has a great track record of integrating schools. That’s because it ends the segregationist practice of assigning students to schools based on where they live. Seven empirical studies have examined the impact of school choice programs on segregation; six found it reduced segregation while one found no visible effect. No empirical studies have found that school choice increases segregation. (Of course, given how aggressively segregationist the government school monopoly is, creating a more segregated system would be a tall order.)

Let’s quit letting politicians draw lines that divide us. School choice is not just a way to deliver a better education to all children. It’s an essential step toward an integrated society.

Greg Forster, Ph.D.

Contributor

Greg Forster (Ph.D., Yale University) is a Friedman Fellow with EdChoice. He has conducted numerous empirical studies on education issues, including school choice, accountability testing, graduation rates, student demographics, and special education. The author of nine books and the co-editor of six books, Dr. Forster has also written numerous articles in peer-reviewed academic journals, as well as in popular publications such as The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and the Chronicle of Higher Education.