Health Care

Kaitlyn Finley | October 6, 2020

Why we pay too much for health care (part 2)

Kaitlyn Finley

[This article is the second in a series addressing the structural problems that plague our health care financing system and how to fix them.]

At every doctor’s appointment, we pull out our insurance card and the money for our copay without hesitation.

But have we stopped to consider why insurance is involved every time we go to the doctor?

Other types of insurance don’t typically cover minor costs. For example, my car insurance doesn't cover my routine $50 oil changes.

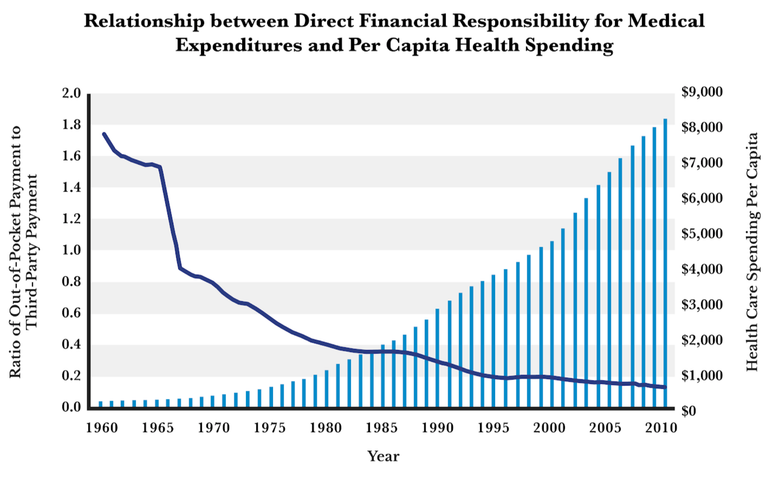

As I mentioned in part 1 of this series, there is a stark inverse correlation between how much we don’t pay out of pocket and skyrocketing medical prices.

Source: David A. Hyman and Charles Silver, Overcharged: Why Americans Pay Too Much for Health Care, pg. 288. Data sourced from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1960 to 2015.”

Why did we shift from paying out of pocket for care to instead relying mainly on insurance to pay for even the slightest ailments?

The Origins of Health Insurance

Unfortunately, the answer has nothing to do with saving money and much to do with power and politics. In her book Ensuring America’s Health, Christy Ford Chapin details how insurance companies became entangled with health care nearly 100 years ago. (Also of interest is her conversation with economist Russ Roberts in this EconTalk podcast.) “Politics—not the logic of the market—positioned insurance companies at the heart of American health care,” she writes.

Beginning in the 1900s, “medical coverage” looked much different than modern health insurance. Instead of insurance companies reimbursing individual doctors for services, different models of delivering care were starting to form.

Various professional associations, labor unions, consumer cooperatives, mutual aid societies, and corporations were contracting directly with multi-specialty physician groups (surgeons, cardiologists, general physicians, etc.) to provide comprehensive care. The group or association would collect funds from members to pay for individuals’ care when needed for serious illness or injuries. Minor ailments were paid out of pocket.

There were no outside insurance companies handling claims; the physicians acted as the insurers. They had an incentive to control costs and also to retain satisfied patients.

The Evolution of Modern Health Insurance Model

However, physicians of the powerful American Medical Association (AMA) decided these group prepaid medical arrangements were a threat to their organized profession and to the art of medicine. To discourage doctors from joining multi-specialty groups and contracting directly with unions or mutual aid societies, the AMA would threaten to take away physicians’ licenses to practice. (The AMA held strict political control over licensing laws and regulations.)

However, in a long series of backdoor deals (which Chapin details in her book) with key stakeholders, including physicians, insurance companies, and politicians, the AMA was forced to compromise with Congress and accept what Chapin calls the “insurance company model” by the end of the 1930s. In this model, individual doctors would be reimbursed for services, similar to today. Later, the Medicare and Medicaid programs were also built to fit this type of insurance model as well.

Today, it’s easy to see how insurance is deeply rooted in the delivery of medical care. “Insurers decide which services and procedures qualify for policy coverage, influence physician pay and hospital revenues by setting reimbursement fees, and shape medical practices by requiring that health care providers follow treatment blueprints to obtain compensation,” Chapin explains.

But it’s not just insurance companies. Employers have also been a key component in the delivery of care through the insurance company model, exacerbating the third-party-payer problem.

Employer-Sponsored Health Care and Rising Costs

During World War II, President Roosevelt directed the National War Labor Board to enact wage and price controls on employers. However, contributions to health insurance and retirement funds were not counted as wages for purposes of the wage controls, meaning employers were incentivized to offer more generous health benefits to attract workers as an alternative to cash pay. This provision catalyzed the increase in employer-sponsored health insurance coverage.

In 1940, 20 million Americans had health insurance. By 1960, more than 142 million Americans were insured.

Today, employer-sponsored coverage is a major source of health insurance for families; roughly half of Americans are covered through their employer, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. In 2017 this tax exemption for employers resulted in $260 billion in lost revenue from payroll and income taxes to the federal government.

Due to the combination of the insurance company model and employer-sponsored coverage, consumers are largely insulated from their health care costs and oftentimes have only a few choices when picking their specific plan. Their concerns regarding costs go only as far as their deductible. Health care costs continue to rise as we let other entities pay most of the bill on our behalf. We are not true consumers concerned about costs, a key factor in a properly functioning marketplace.

“In the employer-based market, not only is a third party—the insurer—paying for health care, but another third party—the employer—is choosing and funding the insurance plan,” health care policy expert Avik Roy explains. “Call it ninth-party health care. In this system, workers almost entirely lack the tools they need to shop for low-cost, high-quality health care services. For the typical worker, 80 percent of health care is paid for through insurance. Without transparency into the price of health insurance, workers lack transparency into the price of health care.”

Shielding consumers from the true costs of health care through the overuse of insurance policies and employer health care plans will cause prices to rise even more, as Charles Silver and David Hyman explain in their book Overcharged: Why Americans Pay Too Much for Health Care. “[E]xcessive reliance on third-party payers has convinced Americans that they cannot and should not pay for medical services themselves.”

Silver and Hyman argue we must change individuals’ mindsets regarding health care financing to fix the system. “To dig ourselves out of this hole, we have to learn to treat health care like everything else. We should pay for most medical treatment directly, the same way we pay for housing, transportation, electricity, water, food, and clothes. Insurance should be reserved for calamities,” Silver and Hyman conclude.

In the next article in this series, we’ll learn how this third-party-payer problem is responsible for not just rising costs but also for much of the fraud and waste within our health care system.

Kaitlyn Finley

Policy Research Fellow

Kaitlyn Finley currently serves as a policy research fellow for OCPA with a focus on healthcare and welfare policy. Kaitlyn graduated from the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma in 2018 with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. Previously, she served as a summer intern at OCPA and spent time in Washington D.C. interning for the Heritage Foundation and the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works.